J. Lorand Matory’s “The Fetish Revisited” Wins J. I. Staley Prize

“I've spent most of my life since I was 13 working very hard to learn other people's languages,” says J. Lorand Matory.

He has just come from a midterm exam in his advanced undergraduate Chinese language and culture class, Chinese being the most recent of the numerous languages he has studied.

“I find it liberating to think in the terms of others who grew up thousands of miles away and have a totally different cultural history, and to try on their ways of thinking,” he says. “How can you understand other people's point of view unless you're trying to speak their language?”

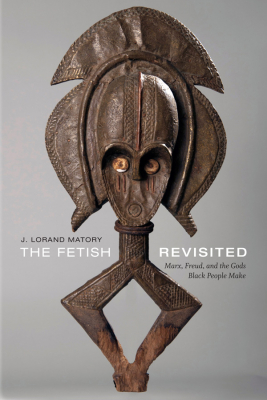

In “The Fetish Revisited: Marx, Freud, and the Gods Black People Make,” Matory, Lawrence Richardson Distinguished Professor of Cultural Anthropology, brings his linguistic curiosity to bear on a re-examination of the term “fetish” and the ways in which this word has been used by scores of Western theorists — Marx and Freud most prominently among them — as a metaphor to criticize injustice and poor logic in the West.

Matory questions the assumption of Europeans that fetishes — as European theorists originally called the consecrated objects of West African Yorùbá religion, Cuban Santería or Ocha, Brazilian Candomblé and Haitian Vodou — represent an irrational spirituality. On the contrary, he demonstrates the rational community-building functions of these human-made gods.

Going a step further, he shows that Marx’s and Freud’s theories have their own fetishistic elements — that is, they, too, assign value and power to things in self-interested ways intent on proving their own version of who owes what to whom in social life.

This fresh viewpoint, coupled with Matory’s exhaustive research, has made “The Fetish Revisited” stand out among the publications in the field of cultural anthropology. The book has just won the 2022 J. I. Staley Prize from the School for Advanced Research (SAR), which was conferred on Matory on November 3 in a special ceremony at Duke.

It is not the first prize won by “The Fetish Revisited.” Matory was also awarded the Senior Book Prize of the American Ethnological Society in 2020 and the American Academy of Religion’s Award for Excellence in the Study of Religion, Analytical-Descriptive Category in 2019.

In addition, an earlier book of Matory’s, “Black Atlantic Religion: Tradition, Transnationalism, and Matriarchy in the Brazilian Candomblé,” won the Melville J. Herskovits Prize from the African Studies Association for the best book of the year. Since coming to Duke, Matory has also received the 2010 Distinguished Africanist Award of the American Anthropological Association and, in 2013, the Alexander von Humboldt Prize, one of Europe’s most prestigious academic awards.

One of the most prestigious awards in the discipline, the Staley Prize is described by SAR as recognizing “innovative works that go beyond traditional frontiers and dominant schools of thought in anthropology.” The award recognizes the most outstandingly and enduringly influential recent books in the anthropology and allied fields.

The field of competition in 2022 included all the books in anthropology and related fields that were published between 2014 and 2020. SAR President Michael Brown, who presented the prize to Matory, called “The Fetish Revisited” “a work of considerable ambition and insight that is likely to prove influential in fields far beyond anthropology, including philosophy, psychology and religious studies.”

“I think the unique appeal of this book is that it analyzes Marx and Freud from an Afro-Atlantic perspective,” Matory says. “In the past, I've published books about the Afro-Atlantic religions of Nigeria and Brazil, as well as one about ethnic diversity in the Black population of the United States. Those kinds of books have a certain market — people who are interested in Africa, people who are interested in Latin America, people who are interested variously in religion, gender, ethnicity, higher education or transnationalism.

“But there is a much broader swath of people who are interested in Marx and Freud and European theory generally. It's almost an expectation in the elite academy that one refers to European theorists as the foundation or touchstone of one's thinking about virtually any topic. So, ‘The Fetish Revisited’ is a new voice in an area of broad and general interest across the humanities and social sciences. It has drawn a broader audience because of that multidisciplinary touchstone in Marx and Freud.”

The book reflects not only decades of ethnographic research Matory conducted in Cuba, Brazil, Haiti, Trinidad, Jamaica, the United States, Nigeria and Germany, but also untold hours of studying the scholarship on Marx and Freud.

“I need to master a very broad literature as I bring together topics that are not usually treated together,” Matory says. “There are people who spend their whole lives studying either Marx or Freud alone. As soon as you weigh in to either of those topics, you're in a minefield, and if you don't recount all of the various interpretations, and cite every intervention, you get in trouble. Writing this book really was a lot of work, and I'm grateful that it was recognized.”

In addition to Matory’s impressive scholarship, “The Fetish Revisited” is energized by his obvious love for his subject matter. His passion for the sacred objects of the Afro-Atlantic religions, as well as the priests and worshippers who create and nourish them, is evident in the book’s illustrations and color plates, which depict much of the sacred art Matory has collected over his career.

These objects are available to the public in an online collection, Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic, which began at Harvard University when Matory was a professor there, but has grown and become an online exhibition since Matory arrived at Duke in 2009.

“Over the years of my field research in multiple countries, I would regularly purchase items, but it wasn’t until I came to Durham that the resources became available to catalog them electronically,” he says. “I worked very closely with the Office of Information Technology at Duke to build an online educational resource that is really multilayered, including videos and ‘virtual guided tours’ that show sequences of related objects and tell stories about the cultural connections among them.”

“There is something unique about this particular collection,” Matory stresses. “It's not a collection of objects extracted from their social context and the social relations that produced them, but one that renews and expands the social relations that give these objects meaning and life.”

One way this is achieved is through Matory’s use of the collection in his popular class, Black Gods and Monarchs: Priests and Practices of the Afro-Atlantic Religions, which will be offered in spring 2023. “I invite priests I’ve known for many years, from as far away as Nigeria and Brazil, to come to campus. They talk with the students in class and deliver a public lecture, and then conduct a ritual at my house where the sacred objects from their traditions are kept alive.

“I'm very thankful for Duke’s support of my research and I'm grateful to the priests who made these objects for me and support this collection and have supported me over the years.”

Matory also appreciates the recognition the Staley Prize brings to the years of painstaking research represented in “The Fetish Revisited.”

“I’m enormously grateful for this recognition because it's possible to do such arduous work and have nobody read it.” He says. “Most of the good work that's done in the world goes unrecognized. So this recognition makes me feel that I am doing the right thing by trying to think through things very carefully and put down all the probative information in an order that emerges clearly only after hundreds and hundreds of hours of work.”